Almost two years ago, I wrote a short article (published here) about combining Agile and Usability practices. I described one way of implementing this combination, a way that today seems a bit too complicated. I have been practising Scrum in combination with Extreme Programming the last few years, which is what is popular at the moment. This article is the first of three (the other two are linked below) which explains how to implement user experience design in Scrum

The Agile manifesto values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

The problem areas have traditionally been the same in design as in software development. A focus on processes, documentation, etc. has prolonged (and sometimes ruined) the project. In many kinds of projects, adapting to agile methods (which means implementing the above-mentioned principles) has proved successful. But how do you apply them to user experience design?

In a waterfall-like project, you have room for a lot of analysis, a lot of design and hopefully also a lot of testing. The simple approach is to scale down everything you’re used to doing. This can be enough for the product you are designing, but there might be a constant struggle to explain designs, keep up with the developers, and actually be able to test anything before release. To solve this, you’ll have to adapt the methods to agile principles and the time-frames of agile projects. If you ordinarily do deep interviewing and Visio-style interface specifications, you will probably need to change the method to something less time-consuming, like time-boxed group interviews, cross-functional collaborative design sessions, as well as swiftly created mockups actually constituting the specification. Also, instead of using a complicated setup for usability testing with many users, do a small-scale test using Guerilla HCI methods.

Apart from lowering the fidelity of your design and adapting your methods, you need to position yourself in the project to achieve a productive agile UX environment.

- You need to have mandate in deciding what is built as well as the overall business strategy, the effects of the product. Create a map that visualises how a design can support the envisioned effects, supported by user stories and prototypes. This map can then also be used to roughly estimate the size of the project, as well as helping developers to estimate tasks. Check out the impact backlog below.

- At the same time, make sure that you synchronise your design work with development, i.e. integrate your usability methods in the development method and be a part of the team. It is possible for the UX practitioner to act as customer to the agile team (or be part of the Product Owner team in Scrum), but communication and design would benefit more from a closer integration. You would then have a better involvement in the final result and the chance to learn from the developer’s knowledge. A collaborative design approach can help you being and staying agile; having continuous discussions about the design instead of detailed specifications will support the core principles of agile methods. Check out sprinting UX below.

To summarise, start thinking and start acting agile. It will be productive and fun.

1 – The Impact Backlog

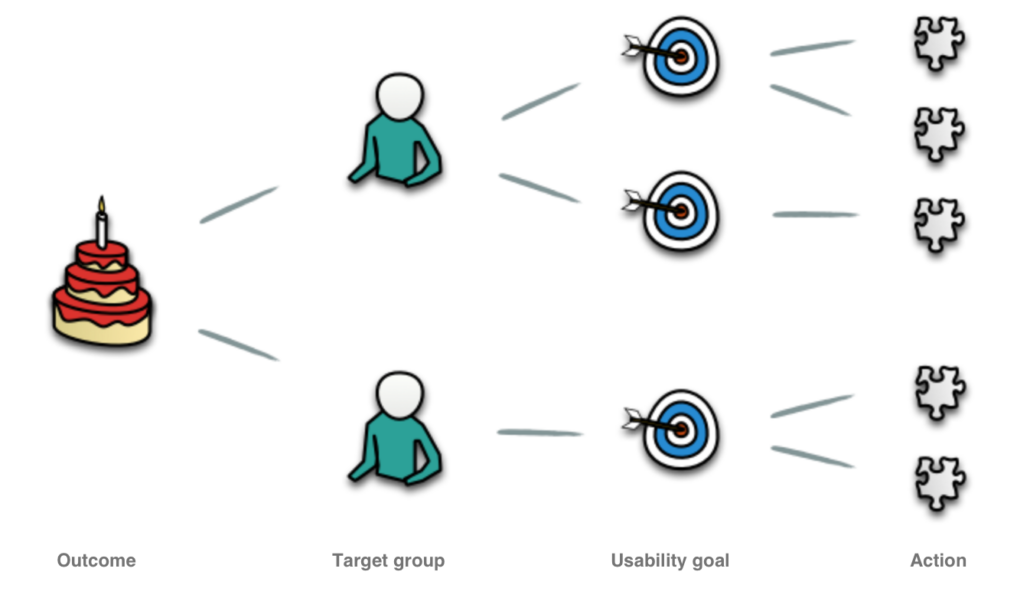

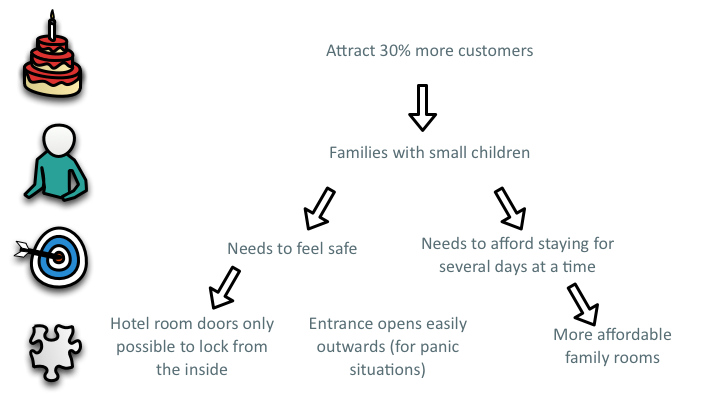

Using the method Business Impact Mapping (by Ingrid Dominguez and Mijo Balic) creates a good base for the Product Backlog in Scrum. The method steers the project towards the expected impact of a product, using a five step method and four key concepts: Business outcome, target group, usability goal, and action.For example, a hotel branch would like to make more money, i.e. get more customers. This is the expected outcome. To achieve this, they would have to convey different feelings to attract the customers, like being classy but at the same time affordable and secure. This is a usability goal. So, when creating the main entrance for the hotel, you would of course like it to function properly, i.e. open inwards to let customers in as well as open easily outwards for panic situations, as well as welcoming the customer and ensure his/her safety. This is the action. This has to be tested to ensure the impact, with real customers. This is the target group. And of course, this target group helps with finding the usability goals and the necessary actions to fulfil the goals as well.

Putting this into a five-step method: Firstly, describe the expected outcomes. The description should contain how to measure the outcome, otherwise it is of low use. Secondly, clarify the user’s goals. Translate the user’s goals into usability goals and measure them. Thirdly, create possible solutions (i.e. the action) to the usability goal. The easiest way is to create some kind of prototype. Fourthly, test in actual use, otherwise the effects will not relate to the actual situation. Especially if you test with a prototype, try to do it with actual users where they would use a real solution. And last, visualize all of this in an impact map, it will be a lot easier to track changes, understand correlations and prioritise.

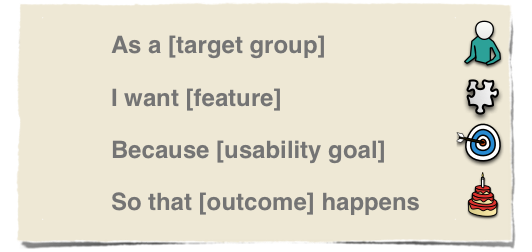

It is widely spread amongst Agile practitioners that, while describing what to do in a backlog item, it is a good idea to explain why this has to be done. This is where Business Impact Mapping fits. Combine the impact mapping that we did above with your common format for a product backlog. It would make it easy to understand which users that would benefit from this backlog item and what effect this backlog item would have on the software in the long run.

An even better approach is to write user stories on a slightly different formats, so that every story on the agile board will show for who the feature is created, why it is good for them and why it is good for the company.

For the whole Agile team, it would then be a lot simpler to estimate each item as well as easier to understand how and why a certain item is prioritized the way it is. This user story will then truly guide the development towards the right product. It’s a win-win situation since UX practitioners also like to connect actions (i.e. production code) to usability goals (and effect), e.g. for easier validation or usability testing.

2 – Sprinting UX

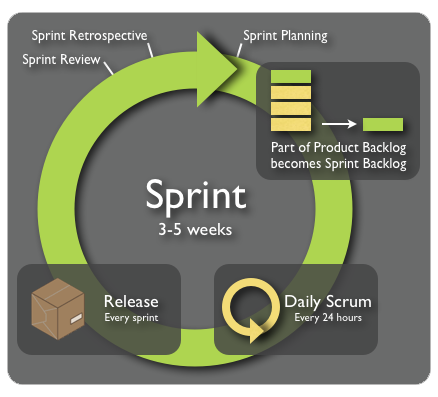

Scrum is focused on the planning and following-up parts of a project. Three roles are specified for Scrum: The Product Owner, the Scrum Master and the Team. The Product Owner is the voice of the customer, this person (or team) has the domain knowledge and the mandate to decide what will be built. The Product Owner is in charge of the Product Backlog, which contains both the plan and the requirements (features to be built, etc.) for the project. The Scrum Master is in charge of making sure that the team follows the Scrum rules and stays agile. This person is an ordinary team member but has great process knowledge and acts as a coach. The Team is a cross-functional group of people tasked with implementing the requirements.

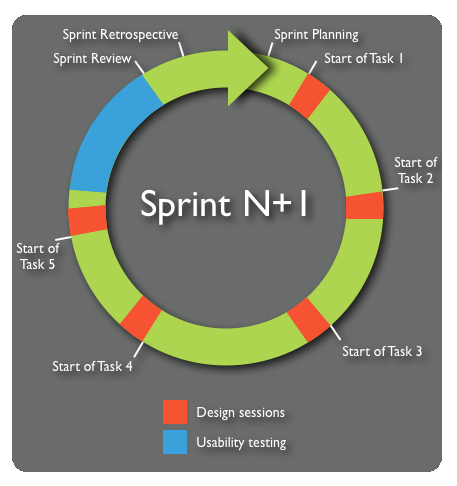

Each iteration in Scrum is called a Sprint, and this sprint usually lasts between 3 and 5 weeks. In the beginning of each sprint there is a Sprint Planning meeting, where the Product Owner presents a chunk of the Product Backlog that he or she would like to see built at the end of the sprint. The team estimates the chunk according to their knowledge and skill, and makes sure it will fit during the sprint. Once the team and the Product Owner have agreed that they have a well-sized and meaningful chunk of features to build, which is called the Sprint Backlog, the team builds it (supported by the Product Owner for requirement details). Each day during the sprint, a very short project status meeting occurs. This is called the Daily Scrum. During this meeting, each team member answers the questions: What did you do yesterday? What will you do today? What might hinder you from doing that today? The reason is to keep everybody up to speed and solve difficult problems as soon as they arise. At the end of the sprint there is a Sprint Review meeting, where the team shows their built chunk and the Product Owner gives feedback. This feedback might then be a part of the Product Backlog and put in the Sprint Backlog for later sprints. After the Sprint Review, there is a Sprint Retrospective meeting where the sprint is analysed and the team can adjust/improve/correct their process before the next sprint starts.

The team sprints until the Product Owner is either content or out of money. 🙂 This requires each sprint chunk to be a potentially shippable product. To make this work there has to be some kind of rough plan as to what will (or might) be released to the Product Owner in each sprint. Hence, the team usually starts by building a foundation (as well as getting the process on track). This sprint is called sprint zero.

As with all agile methods, you are supposed to add to the method what you think is missing. This is why you often see Scrum combined with Extreme Programming in software development, but Scrum in itself has many other application areas. The following is what a combination between Scrum and user experience would look like.

UX Sprint Zero

For the user experience practitioner, the sprint zero should answer why the project shall be built (usability goals and effects) and who it will be built for (target groups, the customer, other stakeholders). This is well-taken care of using Business Impact mapping. Sprint zero should also contain some basic design, to get a good start in the following sprint. This design should be lightweight. This sprint zero is counted in weeks, not months. In a single week of collaborative design, one should be able to sufficiently understand the project objectives and the high level functional scope so that the the size of the project can be roughly estimated and a sprint release strategy can be formulated. It is the same here as in pair programming, two heads think better than one, and you will get automatic quality control of your ideas. You should end up with a rough overall design for the project. Since Scrum is running in iterations, this design will have to be split up in parts that can be designed, built and validated somewhat independently.

If the project is large, break it down and do parts in different agile teams. It is still possible to have only one or two UX practitioners, even if you have two or three teams.

UX Sprint Planning

Since the UX practitioner is tasked with creating usability goals for the project, this also applies to the sprint. This is done together with the Product Owner, who should create a general sprint goal for the sprint. The usability goals will help the team in estimating how long it will take to build each feature.

Creating low fidelity prototypes (mockups) which easily may be brought to a tester, stakeholder or user for informal usability tests gives optimal feedback given the time invested.

If such mockups of the design exist, it will greatly aid the team’s estimation task, since a visual explanation helps understanding than the more formal requirement from the backlog. Also, alternative solutions can easily be discussed and dealt with swiftly using prototypes.

UX Sprint Running

For each sprint, it is not necessary (nor is there time) to create more than the before-mentioned prototype, since there is time set aside during the sprint for communicating details. But exactly how this takes place can be discussed. Here are two suggestions how to handle the communication between UX practitioners and developers during the sprint

- Plan ahead

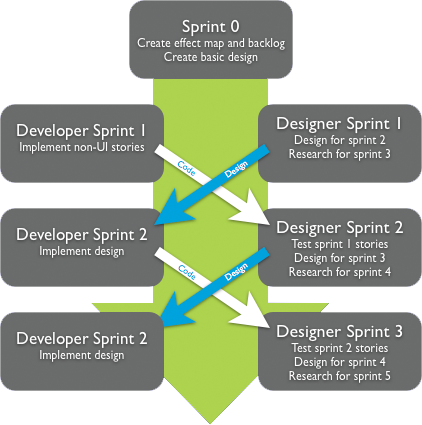

Here, the design and the development are seen as two parallel tracks. The developers run their course as before, and for them to be able to do this, there must be enough designed of the user interface before the start of the sprint where the feature is to be built. This demands that the sprint zero is somewhat deeper than mentioned above or that the first sprint for the developers mainly consists of non-GUI features. In reality, both of these statements are required, since UX design penetrates further down than just the user interface.

Additionally, as shown in the figure, the UX practitioners are one or two steps ahead all the time in this method. While the developers implement design, the features from the last sprint are being usability tested, and at the same time, the research and design for the following sprints are done. The advantage of this approach is the added time for research and design compared to the following suggestion, and this is the reason this might work better for some people.

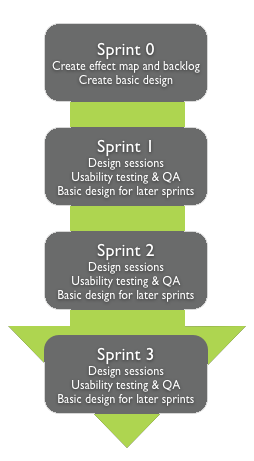

- Incorporate design sessions

And for other people, this approach might be more suitable. In this approach, the detailed design is done in cross-functional design sessions during the sprint. This gives time in sprint zero for deeper research (such as a better detailed sprint release strategy) that pays off later as well as time during the sprint for basic design for later sprints. When a UX practitioner is a team member, this basic design time will be accounted for during the sprint planning.

The design sessions themselves work as following: A session is the start of the building of a feature. It requires the whole team including the Product Owner and UX practitioner (as well as at least a tester), to give everyone in the team an understanding of the design and an appreciation for the process and tradeoffs necessary for a good design. The group designs the GUI together, in as much detail as possible. The rest of the details follow generic platform guidelines, i.e. do not dwell on pixel-specific issues unless they really make an impact on the user experience. The design session is timeboxed (depending on the size of the feature), from 30 minutes to about 4 hours. For a well-defined increment of the product, i.e. a good sprint backlog, it is possible to do a longer design session for all of the GUI design of the features at the start of the sprint.

This last suggestion is advantageous since it gives more time for usability testing and quality assurance during the sprint. This testing can be done when a feature (or a set of features) is finished, but the recommendation is to do it the last week of the sprint. Then you test all the features that have been built so far with select users. In parallel you may run an informal pre-validation test (depending on how many testers and user representatives that are available) since this gives a lot of good input to both usability QA and to the product owner before the sprint review meeting.

Apart from all of the above, do not forget to try adding what works for you today.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!